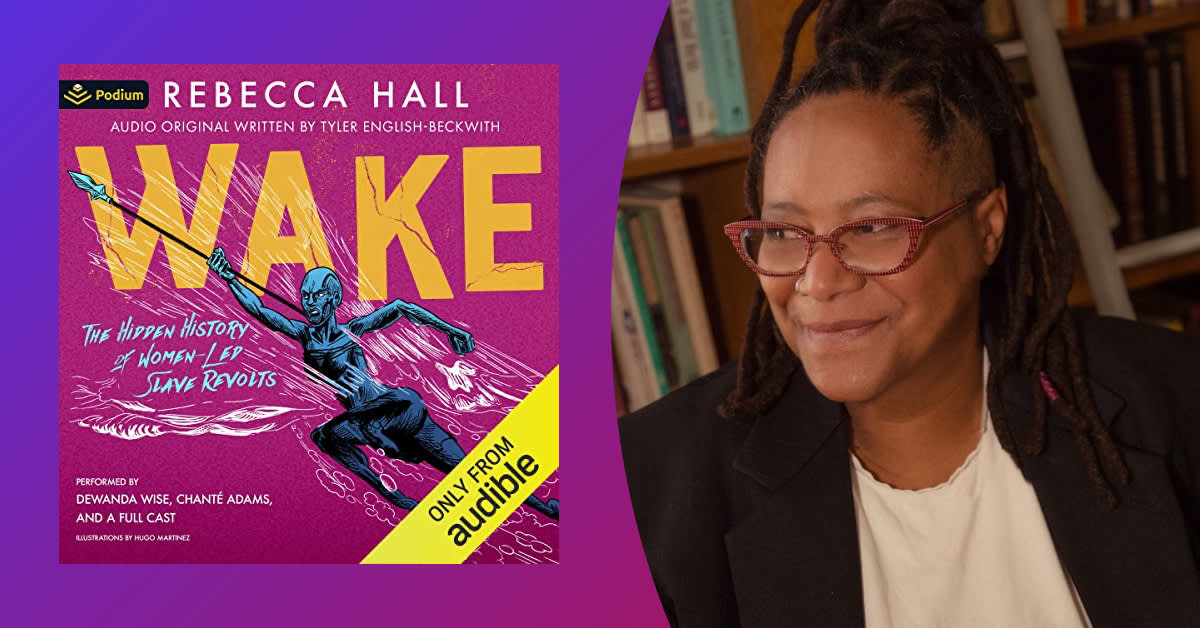

Adapted into an audio original drama by award-winning playwright and television writer Tyler English-Beck along with Rebecca Hall, Wake begins with Hall announcing, "This is the story before the story." In the next scene, we're on a ship where determined enslaved women are planning a revolt. As the audio play continues, we learn that Hall was a tenants rights lawyer before becoming a historian. Academic institutions rejected her for daring to teach historical truths. We meet her students, so rich in curiosity, and share their enthusiasm. Like them, we are learning more and more about these bold women warriors as this extraordinary story unfolds. An all-star cast accompanied by music and sound thematics make for an invigorating, can't-stop-listening experience.

We spoke to Dr. Hall about creating such a bold and significant work.

Apparently, the history of women-led slave revolt wasn’t ignored by just white historians but by Black historians as well, as you seem be the first to do such a deep dive into the subject. Does it take the granddaughter of a slave who happens to be a historian to care enough to do the work?

That is an interesting question. Perhaps. But I don’t question the dedication of the Black scholars who worked to recover the history of slave revolt. The issue here is what shapes historians’ understanding of the field, and this is something called historiography. Historiography is the study of how history is written, and what factors shape the historical interpretation of the past. The first thing I had to do when I began work on my dissertation back in 1999 was to understand this historiography in order to disrupt it.

Historians always write in a social and political context, and this shapes how they write about the past. They also write in conversation with other historians’ interpretations of the past. And it is very hard to see something you have been taught doesn’t exist. My research and interpretation rejected the original idea that women weren’t involved in revolts. Maybe it took the grandchild of enslaved people who was a historian and a feminist who has always looked for women warriors.

For the book, you worked closely with your illustrator. For the audio drama, you worked with the playwright Tyler English-Beckwith. Can you share with us what that process was like?

It was fascinating! I’ve never worked with a playwright before, and Tyler is brilliant. What an amazing talent and skillset. Early on in the writing process, Tyler asked me to record myself talking about all the times I got fired. That was no fun, but Tyler needed to hear how I speak in order to write my dialog. She wrote like four drafts of the script over the course of a year and some, and I worked with her each time to get her started on the next iteration. I’m not used to writing with other people. I learned a lot!

In films about slavery, past and present, the enslaved characters usually have at least a first name. In Wake, some characters only have designations that you found in logs and court records, such as “Indian Man” and “Negro Fiend.” Do you think Hollywood tends to use names instead of titles in an attempt to sanitize the reality of how enslaved Africans were addressed?

I don’t know what Hollywood does, but we can’t always find the names of enslaved people when doing historical research, especially if the chronicler of the events at the time lived in a world where the agency of the enslaved was so entirely irrelevant that they didn’t bother to record their names. What is more common is being able to find the names of enslaved people but still being unable to find very many details about them. In the New York City Slave Revolt of 1712, I could find the names of the women involved from the court records, who owned them, whether were convicted, and their sentence—but not much else. I could flesh out some details about their daily lives by researching the lives of the white people who claimed to own them. By finding where in the city these slavers lived, what they did for work, and what their household composition was, it is possible to find a few details. But the record is frustratingly sparse. Especially for me as I was researching 18th-century slavery.

At any time during your research and discovery of harsh truths, did Dr. Hall step aside and let Rebecca feel the pain and take a break to regroup?

It was my full-time job as a history PhD student to do this work. I also was a mom of a young child. I didn’t have a lot of time to regroup. I tried to take breaks now and again, but it is really hard for me to turn my brain off.