Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly

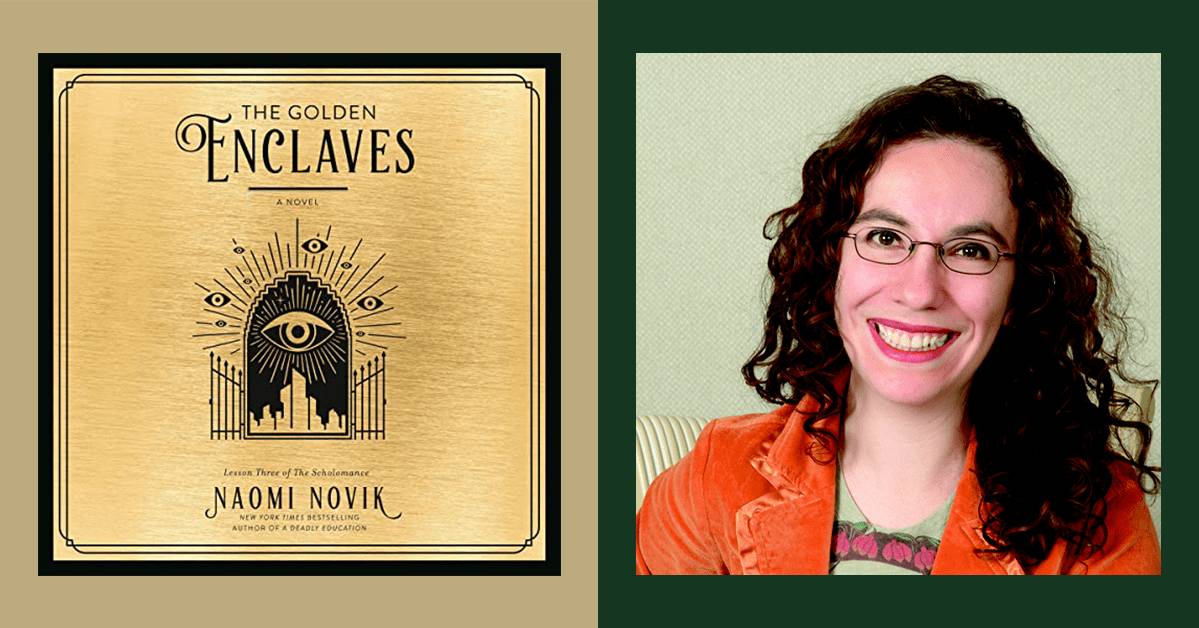

Melissa Bendixen: Hi, listeners. This is Audible Editor Melissa Bendixen, and I am so excited to be speaking to Naomi Novik, the acclaimed author of Audible's top fantasy novel of 2018, Spinning Silver, as well as the Nebula Award-winning Uprooted, a series about proper British dragons called Temeraire, and a dark magical-school trilogy of which the final novel, The Golden Enclaves, is out now. Welcome, Naomi.

Naomi Novik: Thank you so much.

MB: So, first, a little backstory for listeners. The Scholomance trilogy is about Galadriel, or, as we come to know her, El, a teenage witch who is trying to survive through her education at the Scholomance, a magical school that exists in the void to protect magical students from being eaten by Maleficaria, a.k.a. monsters. But El isn't an ordinary witch. For one, she's super snarky, and two, she has an affinity to become a dark and powerful sorceress, and it's way easier for her to cast spells that raze civilizations than it is for her to cast spells that, say, sweep her room clean.

So, she's just trying to get by unnoticed without becoming the dark sorceress that she's been prophesied to be when Orion Lake, the kind of golden boy of the school, and a few other characters bump into her loner lifestyle and shake things up. That's all just the start of Book 1, but we are on the final in the trilogy now, and El and her friends have come a long way since then. So, Naomi, here we are at the end, and this time, it doesn't end with a cliffhanger.

NN: Yes. I know, I'm so sorry. I'm so sorry, okay.

MB: [Laughs.]

NN: I mean, I'm sorry, not sorry, because any book that I write as a series, I at least to some extent in my head have conceived as a single story. And the Scholomance was a single story in my head. But I knew that I wanted to break it into books, for the punctuation effect, that sort of end-of-the-school-year sensation that we all remember from our own school days, even if we're not still in school, and that sense of closing a door on one part of your life and opening it on the next stage.

That was the reason why I wanted it in multiple books, and then, as I was writing each one, Book 1 and Book 2, I wrote the final scene, wrote the final line, and as soon as I wrote it, I was like, “That's it. That's the end of the book." And then I looked at it and was like, "People are going to hate me." So, I'm sorry. I'm sorry. But it was the right place, so...

MB: Are you excited for all the fan reactions now that there won't be a cliffhanger for the end of The Golden Enclaves?

NN: I hope so. A friend of mine, Seanan McGuire, actually said, "You wrote a lot of checks and you cashed them." I hope that's how people feel; that's my goal. One of the things that I feel really passionate about as a writer is that when you finish reading a story, my ideal goal is for you to feel, "Oh, yes. I see all these moving parts that came together that were leading to this place, and now if I turn back and look over the book, or even if I go back to the beginning and start reading the whole thing over, knowing where it's going, it will be enriched. It will be changed somehow. And I'll see how all these pieces were kind of building together to reach this end goal." I hope that's how people feel. That's my dream.

MB: So, El is the central character of the Scholomance series, and I think she might be your most colorful and possibly most opinionated [central] character yet. How did you get into her headspace when you wanted to write from her perspective?

NN: El—and Miryem also, from Spinning Silver—one of the key notes of both of them is anger, right? That, to me, is important in a way, because I often feel like women, especially young women, are urged not to be angry, are taught not to be angry, are taught that getting angry is bad. And, obviously, anger can be a bad thing, but in El's case, she obviously has so much to justly be angry about.

One of the things about El, very clearly for me from the beginning, was the sense of her not being a reliable narrator, in multiple dimensions: that she both was not always reading other people the right way, that she was not always reading herself the right way. She's telling herself stories about herself, about the world around her, in an attempt to survive an extremely nightmarish experience. For me, the key note with El is that if you were actually having El's experience, if the reader, listener, was having the experience of being in the Scholomance, nobody would enjoy that. You would not want to read that book. It's too horrific an experience.

"Even when I have what I think is a plan, even if I think it's a good plan, I will always sacrifice the plan to the truth of the characters and the world."

What I wanted to create was the experience of talking with El about it, in a sense, and having her tell you about it, and she is mediating her own experience. She's telling herself stories. You know, "I'm going to get out. I'm going to get an enclave alliance. I'm going to get a spot in an enclave when I graduate. I'm going to use just enough of my terrible dark powers to set myself up for life." And, of course, she's telling herself this to some extent because she doesn't see another way to make it out alive. But the more time you spend with her, the more it becomes clear that she talks a good game, but that's not actually what she's doing. Telling herself the story is the defense mechanism that lets her survive. And that was one key piece for me about getting into her character, was the sense of her as the person that we're riding with as we go through the Scholomance.

MB: That makes a lot of sense that it would've been a way darker series if we didn't have El as the narrator, because it is a really dark subject matter—children dying in a school and oppressive systems and all of that. And she just has this very flip, snarky way about it that you have a moment where you're like, "Wait a minute. That was actually really intense."

NN: Right. And exactly, I was very often working towards those handfuls of moments, those few moments where her defenses drop and you really see the reality of what's going on and really are with her in those moments. But those were very specifically chosen moments. Those were the points of breakdown where she herself can no longer create an illusion for herself, she herself can't look away or can't escape from the place she’s in in that moment. And those, I think, hopefully, land more powerfully, and give you a sense of sort of the curtain being pulled aside to show you what's really happening, while at the same time, it's not that the whole book is staying in this same utterly horrific, grim, dark register, which I feel is very tiring. I like the flow. I like a kind of movement between emotional registers as I write.

MB: You definitely achieve that. I remember being very terrified whenever the maw-mouth was in the library that very first time in Deadly Education. It does have that flow, totally. So, I feel like we can't really talk about El without also mentioning your narrator for the Scholomance trilogy, Anisha Dadia. She truly was a wondrous fit to play El. Have you listened to her narration?

NN: I have, I have. I am very fortunate that my publisher involves me with the audiobook and with casting. When we were first casting, they sent me various performances, clips of many different potential narrators, and Anisha's immediately just sort of leapt off the pages. It was like, "Yes, that one." And I think the team was all with me on it. She nails that energy of that snarkiness, and yet, at the same time, you get the sense of real emotion, of who El is, this person who is deeply good as well as deeply, deeply snarky and very angry. It's a tough line to walk as a performer, and she just does such an amazing job, and I was so happy. I really was like, "We need her back for the other two." And so I'm really thrilled that we have her on all three books.

MB: Totally. When you were writing The Last Graduate and The Golden Enclaves, did you have her voice in your head at that point?

NN: You know, I can't say that I did because I'm neither visual nor audio-oriented, typically, myself, as a writer. It's all about words. I don't, for instance—this is kind of funny to many people—I don't have a mind's eye. When people say, "Remember a beautiful sunset," for me, there's words. It's words, it's not a visual. I don't actually have that sense of seeing a photograph in my head that I know many people do. And so, for me, it's all words.

I don't hear lines in my head, for instance. When I'm writing, my fingers are doing it. I don't think out a line in my head and then write it down, I'm just typing and the words are coming out through the fingers. I would say speech is the same for me, and I think for most of us, actually. You don't think out a line in your head and then you say it. As you say it, the line is coming. The words are coming out and we're speaking and the thought is taking shape as we put the words to it. And that happens to me both verbally with speech and with my hands as I'm writing a book. Sometimes I will talk lines out to myself in the shower. I work out dialogues sometimes that way, and yet, when I actually sit down to write it, it almost always transmutes completely as I'm going.

I hope that for listeners, when you have a really great performer, when you have someone who's really evoking a character and bringing them to life and inhabiting them, it does create a kind of enriched experience and a kind of embodied experience. For many people, one of the great things about audiobooks is that it adds this additional layer, it adds another artist's work on top of the original work underneath it. What it means is that you get even more the sense, I think, that El is with you, that you're hanging out with El and talking with her as she's telling you this story.

MB: I watched a YouTube video about this and I wonder if it's the same thing, the not having a mind's eye. There's a term for that, right?

NN: Yes, Aphantasia, which I myself only learned of a couple years ago. There was an article in The New York Times that I think had made everybody be like, "Aphantasia, we've heard of it now." And I had not heard of it myself, and I found it incredibly fascinating, because the other piece of it is that apparently it's associated with not having strong memories, strong personal memory of your own childhood. And in fact, that absolutely describes me. I don't have strong personal memory. I remember much more about Napoleon's life than I do about my own childhood. In my family we have a running joke, whenever my sister says to me, "Do you remember that time when X happened?" And I'm like, "No." And that she can make up literally, you know, "You remember that time the fire-breathing clowns burned down your stuffed animal?" I could be like, "Really?" and "Okay. You know, sounds fake, but okay.”

Interestingly, some of the response to it is people will think, "Well, that must make it hard to be creative," where, in fact, for me, it's connected to why words are so important to me, and why building stories out of words comes very naturally to me and is a thing that I love to do, because it's all words. It's all words for me, in my head.

MB: The YouTube video that I watched, it was actually created by a cartoonist, and she had gotten the same kinds of questions, "How can you be a creative and also without a mind's eye?” Because that's how a lot of people that are creators will create, they feel like it's reliant upon that. And I was wondering, “How is that related to being a writer?” And here you are, Naomi Novik, and now I'm thinking, you must be the true pantser [a form of discover-as-you-go creative writing] of us all. You must win when it comes to pantsing. Is it like you're discovering the story as you write it down?

NN: Yes, very much, very much so. I think I've now written about three million or four million words of fiction total over my life. And as you might imagine, as you do this sort of thing, and especially as I've worked at novel length more and more, I do increasingly find that I can see further ahead. I sort of know a little bit more about where I'm going. But the pieces that I see are less the specific things that are going to happen, and more like if you're standing on a high path and you're looking down a hike that you're going to take, and you can see, "Oh, I'm going to hit the top of that mountain, and I'm going to see that tower, and I'm going to end at that waterfall over there, and then loop back the other way past the ruins over there."

And now that I'm sort of like, "I've got a vantage point up here where I can see those places," and I sort of know that I'm going there—but even so, as I go, I don't see all the steps of the path. The path might wind around. I might get halfway to the tower and there could be a fork in the road and a sign that says, "Over here to the lake." I'm like, "Oh, you know what? I feel like going to the lake today. I'm going to the lake instead." I could get to a place and find that the path is washed out and "Well, now what do I do? All right, I'm going this way instead."

Even when I have what I think is a plan, even if I think it's a good plan, I will always sacrifice the plan to the truth of the characters and the world. I would never stick to an outline or a plot or to a specific story beat if it turned out to be wrong for the place where the characters are at that time, because to me, that's inimical to the characters and the world being real. And that's the most exciting part of writing to me. I'm much less compelled by plot in some sort of abstract sense, because plot, of course, is really what the characters do in response to their situation; the actions the characters take are your plot, and what they do and how the world reacts to them. Plot does not exist otherwise. Telling the truth about those things when I come to it is key for me as a writer, as opposed to having an idea and then puppeting the characters around like little dolls, which I find diminishes them.

MB: So, if someone were to ask you the question, "Character or plot?" you would always answer "character"?

NN: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. Absolutely. I don't actually think those things are separate. I think that if they are, then something's wrong and mistakes have been made. If you want the plot to matter, the characters have to be real, and I think that's just fundamentally true.

MB: I didn't know until watching past interviews from you that the Scholomance is something that exists in legends already. That was mind-boggling to me. I thought that you had thought it up, it's such a great name. When you first found the legend, were you like, "OMG, I'm going to use this," or what was that discovery like?

NN: When I first found the legend, I was 10 years old. I found two separate legends that I conflated into one. I got this Time-Life book when I was about 10 years old, I found in my middle school library. And there's this incredibly vivid image of these hooded figures—you couldn't see their faces—in a pitch-dark room, and they were illuminated and there was literally one paragraph caption on the side of this illustration, saying, "The Black School. There was a school of magic where the students had no teachers. The questions that they asked were answered with letters of flame on the walls, and the last student to leave paid with his soul to the schoolmaster, whose name was Satan.” This incredible, incredible vivid image that just instantly lodged in my head.

And then later on that same year, actually, my aunt and uncle had a book, the annotated Dracula. It's this gigantic tome that is the text of Dracula with at least twice as many footnotes as there is text, sort of just commenting, giving color. And there's one line that Van Helsing says about Dracula, which is that “he even attended the Scholomance and learned the dark secrets there.” And in the footnotes, again, it was like two paragraphs of footnotes, saying, "The Scholomance is a legend, an Eastern European legend of a school in the Carpathian Mountains where the students would go and study dark magic, and there were 10 students admitted and at the end of their schooling the devil took the last one, the last graduate, to pay for the schooling of all the others." And that there was a legend that he made this student ride a dragon and bring storms.

And my 10-year-old brain stuck these two together and was like, "This is the Scholomance." And the name stuck in my head, and it was one of those things that I just loved the idea of it. It was an idea that kind of grew with me. The more you think about an idea seriously, when you start taking tropes or potentially fantastical or fairy tale-like things and try to really engage with them, I find that very fruitful. And so, in this case, sort of thinking about what makes somebody go to this horrible place, this place that's pitch-dark and if you leave your odds are one in 10 of losing your soul. You have to experience this legend in its context, which is a Christian context, where the loss of the soul, it's beyond death, it's far beyond death. And so what makes somebody do this? What gets somebody to go to this horrible place?

That makes it very interesting. What basically happened with the Scholomance trilogy is essentially me thinking about that in the context of also thinking about Harry Potter. Harry Potter as the exemplar and most commonly known example of the magic boarding school trope, which again, is this wonderful trope that appears so often in so much fiction because we so adore it for many reasons, right?

What these tropes almost always have in common is that magic does not seem to have a cost. You have to study; the cost is studying, the same kind of studying that you have to do to learn any other subject. But then, once you've learned a spell, you can just cast it and magic happens. And your economy makes no sense once this happens. You can then no longer create satisfying parallels with our actual society, because if you actually were able to just cast spells and do magic and make things happen and create things out of thin air just for the cost of learning the spell, the economics falls apart, and you don't have supply and demand in the same way. Coming to that trope from that perspective, and then bringing in the Scholomance, those two ideas meeting, is where the Scholomance trilogy comes from.

MB: I've also seen you say that when you create a new work, you're creating it in conversation. And that makes me think of, here you are with the magical-school trope, which we all know and love, and it's such a well-known framework. What, for you, is that appeal, and when you created your magical school, are you adding to the conversation or are you asking more questions?

NN: Both. The truth is all art is in conversation. If any piece of art truly stood alone, it would be incomprehensible and boring. What matters about art is that it is in conversation with other pieces of art in some way. It's in conversation with our lives, it's in conversation with the world.

But what I like about showing my work and letting you see it, and not sort of trying to camouflage, and sort of engaging very visibly with a known trope, is that it lets you access the reader's brain, right? It lets you access the listener's brain in that somebody who knows the magic boarding school trope, who likes it, who has read other works, or who has just absorbed it through osmosis, has expectations. They know how the story goes, they know the pieces of the story, and they have those expectations in their head. And as a writer, what that lets you do is instead of just telling a story and your readers receiving it just straight—you can do that, you can change whatever you want, but you could also give them the satisfaction, the pleasure of recognition. I feel like that's a real pleasure.

There's the pleasure of novelty, something new that you've never seen before. There's the pleasure of recognition: "Oh, look, it's that classic piece of the trope. Oh, I know this is going to happen. Oh, it's the end of the year. It's time for the end of the school term, it's finals, it's graduation." And then, at the same time, you can also play against expectations. You can say, "Ah, you were expecting this to happen, but instead we're doing this completely different thing." And then it's sort of like, "Wow, you changed my trope." And that's the pleasure of surprise, and surprise is different than just, "Oh, here's this cool interesting new thing that happened." It's the, "Oh, I was expecting you to do this and you did that instead." That's a different kind of sensation. And finally, there's the pleasure of doing what you expect, but different, turned around.

And so when you're doing work in conversation, it lets you put all those tools in your toolbox, right? It lets you have all those options as a writer, as opposed to just the next thing happened in your own original plot that owes nothing to any other conversation, to any other work. One of the deep pleasures of genre fiction, in general, is that it lets you have all those different kinds of moves.

MB: Totally. So, to write fantasy like yours, I think you must be a master researcher. I'd like to know, what's your process for researching a new story thread? How deep do you go, where do you start, and when do you know to stop?

NN: It depends. It varies very drastically based on the work. So, for instance, for the Temeraire books, I was exhaustively researching many, many specific historical details, precisely because, in that universe, I wanted the dragons to feel to the person experiencing the book [like] real creatures that you could imagine walking, flying, whatever, around in the world, in a bit of a sort of quotidian way. And one of the very powerful tools for accomplishing that is if you scaffold your magical dragons that you want to not feel magical with the trappings of reality. And the more grounded the historical detail, the more accurate all the pieces working together are, and the more that everything else feels true and real and concrete to historical events, historical people. I was looking at one point, “Are there sidewalks in Edinburgh.” This was a three-day attempt to find out. You know, “What's the indoor-plumbing situation?” These kinds of details in the Temeraire universe were very important.

"What matters about art is that it is in conversation with other pieces of art in some way. It's in conversation with our lives, it's in conversation with the world."

With Uprooted and Spinning Silver, on the other hand, it was quite different. I deliberately did not want to pin down the time period. I did not want to be pinned down to a single historical place, because for me, what I was doing in both those books, they are very closely connected for me to my own family, and to my own experience of family narratives, the stories that I was told growing up, and how I took those stories, and how they existed in my mind. And so I often like to say that Polnya, the Poland of Uprooted, and the Lithvas, the Lithuania of Spinning Silver, are not real places. They are the places that existed in my five-year-old mind, based on the stories that my parents would tell, the fairy tales that my mother would read to me, the lullabies she would sing, little flashes of things that sort of coalesced into this unreal landscape in my mind. And what I was trying to do was access that. I was trying to access my own memories.

For instance, the gowns. The gowns have absolutely nothing to do with historical reality. I would make my mother draw me dresses, draw me princesses. And sometimes I would color them, and sometimes she would color them for me, these gorgeous, spectacular ball gowns that didn't actually make any sense and yet were vivid in my head. And those kinds of things, I couldn't research it. That's kind of less of research in the sense of seeking externally, and more an internal excavation.

In Scholomance, the research was typically things like looking at cities, trying to figure out where people were from, trying to get names right, trying to think about languages, trying to make it internally consistent, sort of world building. I couldn't look up what's a spell to clean the floor. Sadly, that's not something you can Google. So, it was more a work of consistency and thinking about structures. So, for instance, the Maleficaria, I figured out at some point, were organized from the kind of taxonomy in my head, like the sort of kingdom, phylum type of organization, that I classified them that way in my mind and was using that structure to figure out what they would be like.

The structure of the Scholomance itself, that was something that came along and became real to me. I think I was almost about halfway through the book, where before then, as I was writing, the Scholomance was a little bit vague. It was the classic school of magic where you think of a sort of Hogwartian-like medieval castle, stone. I knew that it wasn't quite right, but I didn't have a clear sense. And then at one point, one of my beta readers asked me a question about the space, and I had to sit down and figure it out. And I figured out the corkscrewing shape and I figured out the scale, and I realized that it was mechanical, industrial, and that connected to the Titanic in my head and photographs that I'd seen of a tiny, little person next to a gigantic propellor, the sort of sense of something that could grind you up. And that clearly was so right for the story that I was telling that I literally went back to the beginning and rewrote everything that I'd written up until that point, to align with this image that had come up.

That's not research in the classic sense of “I looked through a bunch of books. I read online.” It was a process of I'm writing as I'm going, I'm discovering things about my world. And when I have to answer certain questions, when I have to make a call on something like “How are they getting from the dorm room to the library?” and I need to know something about the internal structure, that is the point where I look at the story I'm telling and have to figure out the right answer based on it. Those two are slightly different things, but it is, in both cases, a matter of trying to figure out what is the right information for your story.

And you asked where do I stop? I almost never stop. When I'm writing, I go and do the research that I need to do at the moment. Or if I'm in flow, there's something that I feel like, "Ah, I have to look this up, I'm not sure about this," I'll typically bold the word and keep on going, and come back to it and then do sort of more specific research. And if I find that something about the research turns up something that makes what I've written inconsistent, I will delete what I've written and write something that is consistent, which I almost always find strengthens the work.

MB: Okay, so it sounds like it's kind of a mesh between a few different things. A lot of self-discovery in there, a lot of discovery of your own childhood, which sounds like maybe that also comes back to the mind's eye thing, writing your truth, writing your family's truth, things like that.

I know that you're also a founder of Archive of Our Own, a repository for fan fiction and so much more at this point. And I wanted to know if you yourself started out writing fan fiction, which I feel is a must at this point. And then, what do you think the role of fan fiction is nowadays in the publishing landscape, considering that it seems to be becoming more and more prevalent that writers that start out as fan fiction writers are becoming published authors now?

NN: I don't know that it's actually becoming particularly more prevalent. I think people will talk about it now. That was, in fact, one of the major goals that we had when we founded the Organization for Transformative Works. I wrote fan fiction as a hobby from high school. I wrote, like, a 60-page Phantom of the Opera fan fiction based not on the musical, not on the original movie, but on a made-for-TV movie. I don't remember any more, I've not been able to re-find it, but I watched it and it spoke to 16-year-old me, and I wrote this unfinished thing on the computer that I was using to type my homework on.

But starting in 1994 when I was a sophomore in college, I found an online fan fiction community, and this idea of telling stories to each other, with each other in community, using it as a way to connect and to express love and tell our own stories, was just so incredibly powerful for me, and I did it for 10 years without ever wanting to go pro. I was going to be a programmer, and now I program for fun while I write books. So, for me, even before I started the archive, fan fiction was an intensely important part of my life. My best friends are people that I've met through that community. My kid plays with their honorary cousins, the kids of women that I met in that community.

And one of the things that was important to me when I did go pro myself, was that I refused to kind of jettison the strength of that community. There was a lot of hostility to fan fiction at the time, the sort of sense of a lack of originality, which, you know, as you can probably tell, I don't believe in that. I believe in conversation, and to me, the difference between a great fan fic story and a great piece of original fiction, there's no qualitative artistic difference. You can tell a great story either way, a deeply meaningful story either way.

There're questions of accessibility, right? How well do you have to know the original source to be able to understand the story? I still write fan fiction. I still read fan fiction. I love it. For me, it's a place of play. It's also just how I respond, honestly, to art. If I love a piece of art, if I find a piece of art compelling and interesting, I want to talk back to it, I want to have a conversation with it. Sometimes I want to do that with fan fic, and sometimes it becomes something different. A great piece of fan fiction should, to me, deeply be about the original source, and deeply be kind of saying something about the original source in a way that really benefits from staying with the original characters, staying with the original world in some way.

With original fiction, it's almost like you've got more freedom, and if you want to go in a different direction, if you want to have a slightly different conversation, if you want to pull in multiple conversational partners. So, for instance, for me, Scholomance, it's the legend of the Scholomance, it's Harry Potter and magic boarding school, and it's The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas by Ursula Le Guin. And it's the political realities, especially of 2016. All of these things came together for me. It's a big conversation. There are lots of people that I'm pulling in, and so it naturally becomes more about the synthesis that I'm making, it becomes more about my voice and my story, and I'm building new characters in a new world to tell it in.

When I'm just writing in fan fiction, it's much more about “What am I trying to sort of illuminate in the original source? What is one question that I have in the original source?” Sort of a narrower focus. But at the same time, doing it, you just learn things. All writing is good, all creative writing, whenever you're sitting down and writing fiction, you're making art, and that's always good.

MB: It's always good. So now, I want to know, what conversation do you want to have next? I'm ready to follow you anywhere, Naomi. Where are you going to take us?

NN: So, I am actually already working on the next thing, which is going to be a little bit of an interesting project for me, because I'm sort of letting go of my total discovery mode a little bit, in that I am doing a secondary world fantasy, meaning a world where I’m creating an entire new world. So, sort of Middle-earth, Narnia, those sorts of things. I'm literally building the map of the planet from the ground up, with the help of a cartographer. We're mapping the biomes and the ocean currents and the prevailing winds.

I'm going to sort of build the history of this world, build the cultures of this world. And then I plan to start telling the story inside this foundation. I'm fairly far along in the process of laying down this foundation, and I'm fairly hopeful that it will be a kind of fruitful experience. I think of it almost in a gardening sense. I'm hoeing the ground, I'm putting in compost, I'm turning over the soil, and I'm sprinkling some seeds, and then, as things grow, I'm going to be like, "Oh, I choose you" and “I'm going to trim back these other plants.” So, it's going to be a little bit more of a controlled riot.

It's going to be called Folly. It's going to be a lot about how places and people shape one another. How homes and the families that live in them shape one another. I think it's going to be about storytelling itself, and about the universe of possibilities in a way. And a desire to write better stories than the ones we are given. That's sort of my high-level feeling. I might be totally wrong about this, we'll see, but I think that's what I'm seeing from up on my current mountaintop. That's what I hope is up ahead.

MB: Wow. So, it sounds like this is kind of a new process for you. When before, you were saying you write with this idea of the pathway and you can choose a different path. Now you've created all the pathways and you can just see where you're going to end up.

NN: Yes. That's kind of what I'm going to try, and we'll see how it works.

MB: That's very cool. I'm so excited for it already. And I loved the Scholomance trilogy, I love Spinning Silver, I love Uprooted, I love Temeraire’s series. I have to say, Naomi, you are one of my favorite authors of the past decade, and thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today.

NN: Thank you so much. That makes me so happy. And this was a lovely interview, so thank you so much for that.

MB: And listeners, you can get The Golden Enclaves and the Scholomance trilogy on Audible now.