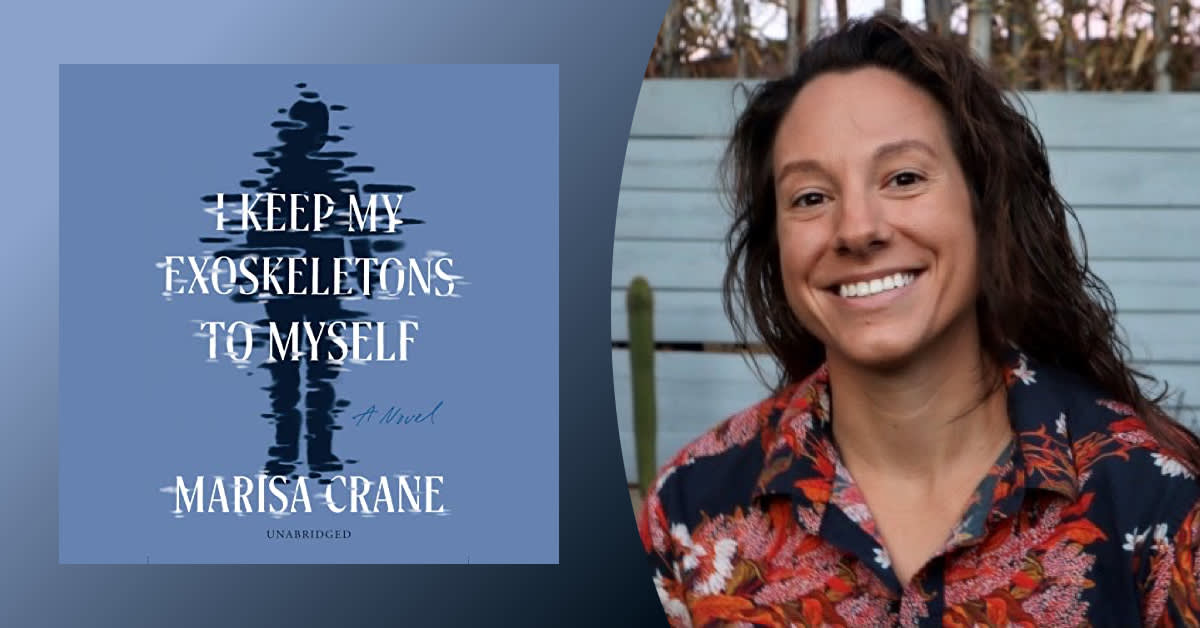

The moment I heard about I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself, it shot to the top of my TBLT list. From the eerie poetry of the title to the premise about a surveillance state in which the shadows of former misdeeds are literally visible for all to see, Marisa Crane's debut novel sounded like a wild ride—and then the accolades started pouring in. I was lucky enough to chat with Crane (they/them) about the inspirations behind the novel, their thoughts on narrator Bailey Carr's performance, and some of their current literary obsessions.

Audible: I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself feels wildly attuned to our current moment. How long was the story brewing in you, and what inspired you to come up with its sci-fi premise?

Marisa Crane: The story was brewing in me for many years, though I wasn’t fully aware of it for much of that time. I’ve always been very interested in shame and how it affects us—our behaviors, feelings, self-esteem, relationships, decisions, etc. And for most of my 20s, I was dealing with debilitating shame, even going so far as to refer to myself as a monster for the people I’d hurt in the past. I thought I was undeserving of grace, love, and care, though I believed everyone else deserved these things.

I say all that to say that I ended up writing a little snippet that went something like this: “If the shadows of everyone you’ve ever hurt followed you around all day every day, would you still be so reckless with other people’s hearts?” It was directed at myself, a means of shaming myself into behaving better. But of course, that didn’t work—I only felt worse, immobilized by shameful memories. Years later, the first line of the novel came to me one day: “The kid is born with two shadows.”

I wasn’t sure what it was at first, but it wouldn’t leave me alone, following me and nipping at my heels like a bossy little dog. Eventually, I connected it to the short poem I’d written, and the world of the book began to develop: In lieu of prison, wrongdoers are punished with an extra shadow for each “crime” they commit (I say “crime” because the government is corrupt, much like ours). The extra shadow has two purposes: It’s a forever reminder of what the person has done, as well as a warning to others.

“If the shadows of everyone you’ve ever hurt followed you around all day every day, would you still be so reckless with other people’s hearts?”

Your writing is gorgeous, which is not surprising considering your poetry background. How did the second-person perspective, framed as a letter to the narrator’s late wife, come to you?

Thank you so much! From the very beginning, the novel was always written as a letter to Kris’s late wife, Beau—a POV I tend to refer to as first-person direct address. I think this was the natural POV for this book because it started out, in a way, as a way to explore my own fears related to family-making and parenting. My wife and I had just begun talking about getting pregnant when I started drafting this book and I was afraid of so many things: What if I was an awful parent? What if I didn’t feel connected to my baby? What if I messed them up? What if I was too selfish? What if my wife and I don’t get quality time together anymore? I began to spiral, my mind playing the worst-case-scenario game on repeat. One of the places my mind tended to go was this lonely, grieving place—what if my wife died during childbirth?

I channeled a lot of those fears into this book, and it felt natural, then, that I would frame it as a letter from Kris to a fictional version of my wife. It felt like an intimate conversation that the reader is privy to, almost voyeuristic in a sense. Plus, Kris needed someone to talk to, especially early on in the book when it’s just her, her newborn baby, and her grief and confusion. She hadn’t been prepared or ready to lose Beau (who is ever really ready to lose someone?), so she clings to the only communication she has left.

My wife and I had just begun talking about getting pregnant when I started drafting this book and I was afraid of so many things: What if I was an awful parent? What if I didn’t feel connected to my baby? What if I messed them up?

Narrator Bailey Carr reads the audiobook of I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself. What did you think of her performance?

I was just blown away by her ability to capture Kris’s voice so well, especially with all of the complicated emotions she’s dealing with at once—anger, grief, fear, shame, despair, and helplessness. It’s beautiful to hear this struggle played out in the narrator’s performance.

How has your own experience with queer parenthood surprised you, shaped you, and (presumably) inspired some of the themes in this novel?

I actually wrote I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself before I became a parent. We were in the beginning stages of talking about family-making. Like I said, in a lot of ways, the book became a manifestation of my own anxieties and fears. But one thing that did surprise me about becoming a parent was that none of my anxieties about being a good parent were warranted. Not to say that I’m the world’s greatest parent, but I mean, I found it so laughable that I was ever concerned I wouldn’t feel connected to my baby or that I would be too selfish. The second my child was born, something shifted in me, creating all the room in the world for this new little person.

One of the recurring “callbacks” in the book is surrounding this notion of a “we,” this powerful, charged word. I think, in the past, I’ve been afraid to become a “we,” not wanting to lose my independence, not wanting to rely on others so much—but finding such a loving partner and raising a child together has softened me a lot and has allowed me to think in terms of “we.”

It was interesting to draft the book without a child and then work on revisions with Alicia, my Catapult editor, after my child was born, because I had a new perspective when approaching Kris’s experience and relationship to her kid. And it was almost harder to channel those moments of Kris’s ambivalence related to parenting since I didn’t share that feeling. But it also gave me a new appreciation for the challenges she overcomes and the connection she builds with her kid, in spite of their circumstances.

As a queer parent, one thing that has continued to surprise me now that my child is two years old is that every day I feel a bit more tenderness for the sperm donor. Before my wife was pregnant, I felt grateful for his contribution but also very determined to prove my own status as parent and even sort of competitive with him, like, "I’mmmmm the real parent, you’re just DNA." But now that I’ve gotten to raise this beautiful, fierce, hilarious toddler, I feel a deep sense of appreciation for the gift this sperm donor gave us. And sometimes I find myself sending him short thank you letters in my mind: Thank you for this book-loving kid, thank you for this kid who says “Mozzy-nowwwwwww!” whenever he needs me (Mozzy being my parenting name). It’s been surprising, but also really nice, and healing.

The kid is absolutely one of my favorite characters in recent memory. What inspired her, and how did she surprise you as she grew with the novel?

The kid is, in part, a composite of many different children I’ve been fortunate to know and work with in my life. For a few years, I was a behavioral and mental health worker with young children and adolescents in a school setting and in a partial hospitalization program (partially the inspiration for Kris’s job and the “troubled kids” she works with). I’ve also coached children and teens of all ages. There are so many quotes of the kid’s that children have said to me, things that have stuck with me for years and years, either for their wisdom or humor or both. The kid is also a bit of an experiment for me in wishful thinking. As a child, I was nervous, anxious, and clingy. When I dreamt up the kid, I wanted to write a version of little me that wasn’t any of those things, the me I wished I’d been, a me that I deeply admire.

The kid surprised me in many ways, but her resilience surprised me most. I think because it isn’t the unhealthy type of resilience that comes from being forced to push through unimaginable pain without expressing it or dealing with it, the type of resilience kids are often rewarded for. It's the real kind of resilience, her ability to create and connect and overcome, despite despite despite.

I was just blown away by [Bailey Carr’s] ability to capture Kris’s voice so well, especially with all of the complicated emotions she’s dealing with at once—anger, grief, fear, shame, despair, and helplessness.

What’s the last great book you read or listened to? And are there any novels you’re especially pumped about for 2023?

The last great book I read was How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu. It was, of course, almost too close to home given that it’s about a pandemic, but I was blown away by the creativity and tenderness and strangeness of this novel. There’s a chapter called “Pig Son,” in which a pig that is growing human organs for dying kids gains the ability to speak, and this grieving scientist who has lost his son bonds with this pig. I don’t think I’ll ever stop thinking about that chapter. It broke my heart a million times over.

It’s also hard to list just one great book. A few more include Sirens & Muses by Antonia Angress, Exalted by Anna Dorn, The School for Good Mothers by Jessamine Chan, and The Boy with a Bird in His Chest by Emme Lund.

There are so many 2023 novels that I’m excited about. I’ve been fortunate enough to get sneak peeks at advanced copies for Richard Mirabella’s Brother & Sister Enter the Forest and Ruth Madievsky’s All-Night Pharmacy, both of which are incredible. I can’t wait for people to get their hands on them. I also cannot WAIT for Chain-Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah and Big Swiss by Jen Beagin. And I have heard nothing but amazing things about Dykette by Jenny Fran Davis. I am really sorry that I have no chill but last two books, I promise: I’m super stoked about Please Report Your Bug Here by Josh Riedel and Where There Was Fire by John Manuel Arias.