Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

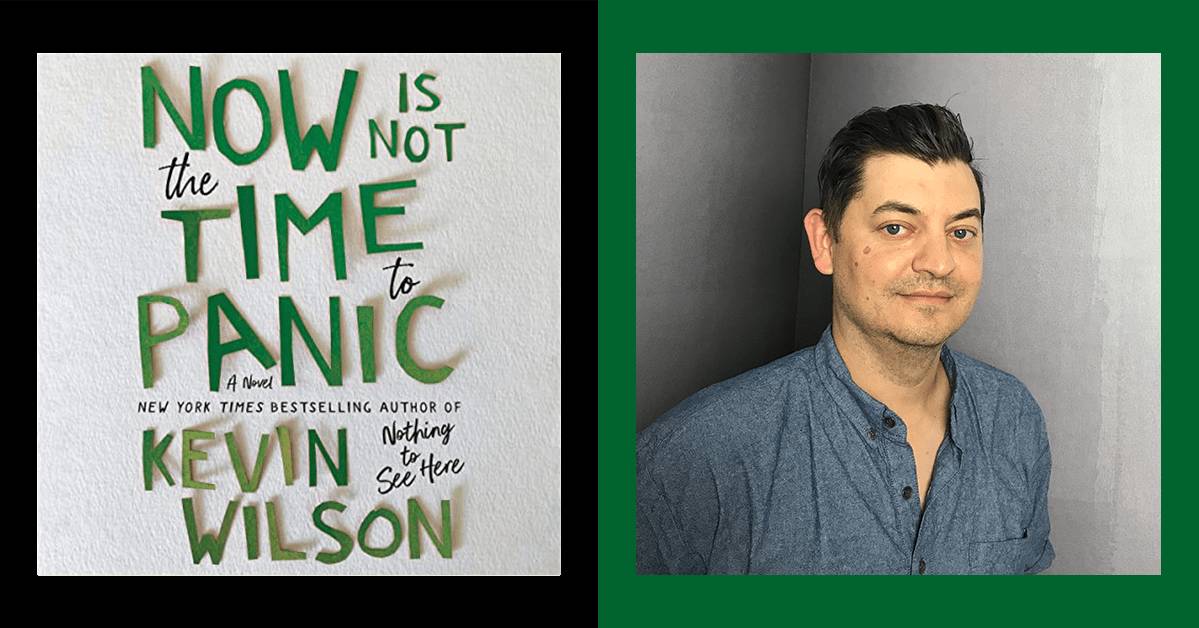

Tricia Ford: Hello, everyone. This is Audible Editor Tricia Ford, and with me today is Kevin Wilson. He's a bestselling author of books you probably know, books like The Family Fang, Perfect Little World, Nothing to See Here, as well as two books of short stories, all available on Audible, by the way. We're here today to talk about Now Is Not the Time to Panic, his latest novel, performed by Ginnifer Goodwin, who you may know from her TV and film roles on Big Love, Once Upon a Time and Zootopia. There's a bonus author's note read by Kevin Wilson himself. Welcome, Kevin. Thank you so much for being with me today.

Kevin Wilson: Oh, thanks for having me.

TF: Now Is Not the Time to Panic is exactly what I expected from you. And I loved it. I was a big, big fan of Nothing to See Here and love this one equally. It's so great. It's set in 1996 in a small town in Tennessee and it tells the story of two aspiring young artists, Frankie Budge, 16-year-old outcast, and Zeke, also 16, who's the new guy in town. Over the course of one summer, they meet, sparks fly romantically, and they create art together. This artwork that they're working on, I know it has a very special origin story. So, I'd like you to share that with us, if you can.

KW: Sure. So, there's a phrase that recurs throughout the book that comes from my own personal life, which is, when I was in college I was rooming with a friend. His name was Eric. He was older than me. He was just spending the summer in Nashville before he moved to LA to become an actor. We would make films together, him and my cousin and me. He was one of the first people my age who thought of art as a thing that could be made, that felt attainable to me. And I just was so enthralled with him.

And I had this summer job where I was transferring this policy and procedures manual online, so I was just writing this whole thing out in HTML. It was super boring. And I just started inserting random lines into it, just because I thought no one would notice. And I kind of wanted to know if anyone would notice. And Eric said, "You should put this line in there." And he said, "The edge is a shanty town filled with gold seekers. We are fugitives and the law is skinny with hunger for us." And it really was just a tossed-off little silly thing, and just the way my brain works, it just burned into my brain. And I put it online and I thought, "Okay. Well, that was fun." And it just stayed with me. And I say it all the time in my head. I actually put it in my first novel, The Family Fang. That line is in there. Every time I think I'm done with it, it keeps coming back. And so, finally, I thought, "What if I just wrote a whole book about this line?" I didn't know if that would be of interest to anyone but myself, but I just wanted to try it. And that's what started, is pulling this thing from my life into this fictional world.

TF: I love that. This line, and the art that they create using it, really does have a huge impact. And the story is really Frankie, who's what I would call the central character. She's now a grown woman in her thirties, happily married, children. And she's looking back at this formative summer. What inspired you to create Frankie? Where does she come from?

KW: Well, it comes from me, I think. I think there's two things happening in this book. One is, it's a coming-of-age story. Frankie is remembering the summer where her life changed, where she met this boy, where she learns that she wants to be an artist. I love coming-of-age stories. But I'm 44, right? And so as fresh as that coming-of-age story is and how much I love it, that's not my life now. I have kids, I've made a life for myself. And yet, there's something really seductive about looking back into the past after the fact and trying to pinpoint, “Here's where it changed.”

"I love coming-of-age stories. But I'm 44, right... that's not my life now."

It's not that you can change it. You can't go back. But there's something seductive about living inside it for a moment and saying, "Ah, this is the line of how I got from there to here." And so it's a coming-of-age story, yes, but in more ways it's looking back on your life, the life that you've made for yourself. For Frankie, it's an artist who's made a life and wants to figure out “Here's how I got here.” And that's me too. That's what I'm doing all the time in my own life. So, it just felt like a natural thing to write about.

TF: That's interesting to me, because Nothing to See Here also had a female central character. Why do you think you made Frankie female and not male?

KW: All four of my novels have a female [as] at least one of the two primary characters. And you'd think after this many years I'd have a better answer to kind of explain it. The more I think about it, for whatever reason it just is a natural voice for me to get into these characters, and they happen to be female. A lot of times I'm taking some tiny personal kernel of my own life, and so it's a way of hiding myself in the story to get a little distance, so no one thinks, "Ah, this is Kevin." It's silly, but that feels like if I can have just that little bit of distance, then I'm really creating a character, not just using myself in the story.

The other thing is just there's something seductive about writing outside of yourself to write a character that's slightly beyond you, because it's dangerous, right? Not super dangerous, but you always run the chance of getting it wrong, or that something doesn't feel correct. And it means that you have to pay a little more attention to creating that character. You have to think about nuances beyond yourself. And I think that keeps you a little bit more alert as a writer, that you don't just fall into, "Well, this is how I see the world. This is what it should be." You're constantly mindful of, in every situation, here is a character that's outside of you, what are they noticing or what are they contending with that you yourself aren't? I like that. I think I need that a little bit.

TF: That's really interesting, because she is such an authentic 16-year-old. I could definitely identify with her. There's a lot of universal themes there. I think the attention to detail really does shine through. Now, speaking of strong female leads, Ginnifer Goodwin, amazing actress. How did she become involved in this project?

KW: I love audiobooks. I listen to them all the time and I feel incredibly blessed that I've had these incredible audiobook narrators along the way, Thérèse Plummer and then Marin Ireland. And I know for this one, Harper Collins and Echo, they wanted someone who had some connection to the South, you know? Someone who knew Tennessee in this time. And they had a list of narrators that they thought, "This is our wish list. These are people that are all great. They would all be fantastic. They all have slight variations in how they would do it." And Ginnifer is from Memphis. There is that connection. And obviously I knew her work as an actress. And my kids just jumped up and down, because she's Judy Hopps from the Zootopia movie. When I heard her voice, I just thought, "Oh, this is lovely. This would be perfect for Frankie." The precision of a slightly sarcastic voice that's held over from her teenage years, even though she's an adult. I was just really jazzed and really excited for her to do it.

TF: She's great. Perfect casting.

KW: Oh, good.

TF: Another thing I've noticed in more than one of your books are multiples. Frankie's brothers are triplets. There's the twins from Nothing to See Here. Where does that come from?

KW: When I'm trying to write, oftentimes I have a character who feels slightly outside, like a loner. Like, in Nothing to See Here, we have Lillian who is charged with taking care of these twins. And she herself is an only child who's been kind of neglected by her mom and there's something for her where she thinks these two twins have a difficult life, they're unloved, but they have each other, right? And in this story, Frankie, her three older brothers are triplets and they're super aggressive, super physical, not in touch with their emotions. And yet, even though I don't think Frankie wants to be them, she realizes that they have a world unto themselves and she has nothing. I write a lot about the bonds of brothers and sisters, you know, siblings. And yet, even within those little families, there's separation within it.

"When I'm trying to write, oftentimes I have a character who feels slightly outside, like a loner."

TF: These boys are such a force of nature, and Frankie clearly loves them and understands them, but is so different from them.

KW: If you're a sibling, no matter what, you're never going to escape that bond. And I don't know that you want to, but you're always thinking about yourself in relation to these other people. And so for Frankie, her brothers are wild. They're feral almost. And that's the expectation for them, that they will cause trouble. And so for Frankie, in the summer where she's the one who creates the chaos, it's more exciting to her or more interesting because she's always been the quiet one, the one in the background as her brothers make a mess. I don't know if that moment resonates as much if she didn't have that relationship where she's always had these three brothers who were out in front clearing the way.

TF: Now, Zeke, where does the inspiration for his character come from?

KW: The moment I knew I wanted to write about Frankie, you need that catalyst, right? She's stuck in this tiny town. She feels trapped. She's loved by her family, but she's outside of it in some ways. And so I knew someone's got to blow into town and kind of create a little bit of transformation. I knew I wanted this boy. And there's this moment, too, where you have other people that tell you these things, like, "You can become anything you want." Your mom's telling you you're smart and you're capable. I had teachers that were kind to me and they really were transformative, but going back—and this is not the story of me and Eric, but Eric was someone my age who for the first time was like, "Art's possible. You can make this." And it felt more meaningful to have someone of my age tell me this was attainable. So, when Zeke shows up in this town and Frankie says, "I want to be a writer" and he's like, "I want to be an artist," they gain strength from each other, right? They know that they can be honest. All along, when I thought of Frankie, I knew I needed someone, and Zeke just kind of appears in town and I thought, "Oh, I'll use him."

TF: It works. They've got good chemistry as well. Now, with that line of the role of art and personal transformation, I feel like as the person taking in the art, listening to the audiobook, it's a reminder for us too. So, how does reading other books, listening to other books, other forms of art that you experience in life, how does that play a role in this transformation versus being the creator?

KW: That's a great question. I love that, and I think about it a lot, too, because before I ever even thought about writing, growing up in Winchester, Tennessee, in the middle of nowhere in this rural space in the ‘90s, [writing] felt unattainable. But books were attainable. I could get them. I couldn't get everything that I wanted, I could find these things at the library. And I was a pretty isolated, anxious, weird kid, and books were this window into a world beyond me. No matter what the subject matter was, no matter how terrifying the stories were, no matter how difficult the emotions were, there was something comforting about reading a book and thinking, "Okay, the world is a little less scary to me now. I can extend myself out just a little further than I could before, because this book helped me understand it."

If I had to choose between reading and writing, I'd choose reading, because it's limitless. And every time I read a book, I feel like my world gets a little bit bigger. I need that so that I don't just live inside of myself forever. That's the connection to writing. Eventually you feel so transformed by all these works of art that have meant something to you that you just want to try to make something of your own just to let it touch up against those things. And so I don't think I would've written if I hadn't loved reading. I wouldn't have even tried.

TF: That's super interesting. As someone taking in the book, it rekindles those moments in life where you discover what's possible, in a new way, as a grownup. You need those reminders sometimes, because life-changing things are possible at any time. While you'll never go back and be that 16-year-old again, sometimes you have to go talk to your 16-year-old to be reminded of what's important.

KW: Yeah. And now I have kids. My son's in high school, my oldest son, and it's not like I think, "Oh, our experiences are exactly the same." But it helps me to think about those times, where I try to strip off everything that's happened in the last 30 years. I try to imagine, "Okay, before all of that, who was I?" And it becomes really helpful for me to think of my son and say, "This is who he is in this moment. Of all the things that will come, here he is right now." I don't think there's anything wrong with checking back on yourself in the past to remember all those lines that connect to who you are now.

TF: Yeah, I agree. One of the things I love about the audiobook is your afterword, which I think honestly you could listen to before or after listening to the book. In that, you reveal a Tourette’s syndrome diagnosis, and I found it super interesting to see how that realization changed your understanding of your previous 16-year-old self. Do you feel like you understand yourself better for having a diagnosis, or how has this affected your creative process?

KW: Yeah. I always had anxiety. I'd been medicated and always been aware of it, that there were things I needed to be mindful of in order to keep moving forward. But it wasn't until I was an adult in my mid-twenties that I got diagnosed with Tourette’s. It was hard to then go back and say, "Ah, this all makes sense now." But it was just helpful for me to move forward. To think, "Ah, okay. This makes sense. This is how I can handle it." And once you have a name for it, you start figuring out how it fits into your life, but also how it may have affected your past.

But the way it affects my writing and always has is I'm repetitive. I go back all the time. I play things over and over. I say things over and over. My mind is a kind of carousel where things just come and then they flash by and I know it's coming back. And that was really scary as a kid. You have these images that you don't want, or little phrases, or little stutters and ticks, and you know it hits and you know it's going to come again, but you don't know when. That's really scary when you're young. And it's scary now as an adult. But one of the things that helped me creatively is if I know something's coming back, if I can hold it in my head, I can let it go knowing it'll come back. And when it comes back, I can do something slight to alter it. And then it'll come back again.

That's how I tell stories. I tell it in my head over and over and over again, and each time it gains a little depth, a little more nuance. That's Tourette’s, but it's helped me as a writer to calm myself, to know that I'm going to keep getting a chance at it. I've held that phrase from Eric since I was, what, 19 years old? It's going to keep coming, it'll never go away. And so each time I figure out a new way to keep it alive without letting it ruin me. And that's what this book in some ways was. I wanted to write it out, so that it didn't turn into something that I didn't want it to be.

"That's how I tell stories. I tell it in my head over and over and over again, and each time it gains a little depth, a little more nuance."

TF: Wow. We all have variation in how we think and process the world around us, so that's a beautiful thing about fiction is you get to jump into someone else's brain for a while and it kind of changes your thinking in a profound way. Now, knowing that you're a fan of audiobooks, I did want to ask for some recent listens that have been your favorite, and when and where you tend to listen, and what are some of your all-time favorite audiobooks?

KW: Oh, that's a great question. I do love audiobooks. The narrator who read Nothing to See Here, Marin Ireland, was just so wonderful. I don't listen to the whole audiobook of anything I've written. That seems weird, but my oldest son was like, "Could we read it together?" We read at night. And I thought, "Oh, I don't want to read my own book out loud to you." But I was like, "We can do the audiobook." And so I listened to it, the entire time with my son Griffin. It was this wonderful thing where it was like, "I didn't write this." You know? "This is a book that I'm listening to." And it was lovely to hear it in her voice. She's wonderful. She did Rumaan Alam's Leave the World Behind and she's so great at that. And Cynthia D'Aprix Sweeney's Good Company. She just kind of inhabits those books in such beautiful ways. And I love those two books a lot. Another one, he's not like a professional, is John Darnielle, who's from the band the Mountain Goats, and his new book, Devil House, I just love his voice. The way he reads his own words, it's one of the rare times where an author is qualified to do the work [laughs].

And then the last one that I just recommend to everyone, I love it so much, is Steph Cha's Your House Will Pay, which is a kind of mystery. It takes place in California and it has two competing narrators, one African American and one Asian American. And the interplay between those two narrators’ voices and the way it switches back and forth. The book itself is incredible, but, again, it's one of those books where when you listen to it, because of these two voices intertwining, it just makes the experience feel special. I don't think an audiobook necessarily makes a bad book good, but a really great audiobook narrator can make an incredible book feel even more special.

TF: Totally agree. So, I love this book. I know it's brand-new. But I have to ask if you have anything new in the works and what that might be.

KW: Like, the way I talked about my brain, it's all recurring. When I wrote The Family Fang, which was my first novel, I didn't know if I would ever write another book again. I just thought, "I'm going to put everything I can think of into it." And so I put that line that's in Now Is Not the Time to Panic. I put it in there and then after the book was published I was like, "Oh God, I have to write another book.” And now that just seems to be the way that I work: I go backwards and figure out how to take something out and make it new. And in this book, Frankie has written an adult novel about a woman picking up all of her half-siblings to go to their father's funeral or whatever. You’re bound by blood, but you've not lived together. And what does that mean? How much of a family are you? And I kept thinking about that. I knew it was recurring, because it kept coming back.

I'm working on a new novel about half-siblings, a half-brother and half-sister discover each other. They have the same dad, who every 10 years leaves his family and starts a new one. And he's been moving to the West Coast steadily. And so the book is them going cross-country to find all their half-siblings to pick them up and drive them towards a reckoning with their dad. And it's fun to write because I really hate making my characters move. Most of my books, the characters are kind of isolated. They stay in one place forever. And with this I thought, "They'll get in this car and so I'll get expansiveness. They'll travel the country, but they'll still be in a car together and I'll get that tightness and isolation," which is how I work best, with a little constraint. So, we'll see. I've started.

TF: All right. Can't wait. Now, I know you're a teacher, a creative writing professor, specifically. I'm curious how your students influence you. I know you have a lot to teach them. But what are they teaching you?

KW: I want to teach them about craft. I want to show them books that I love. But the more and more you teach, the more you realize that your job is not necessarily to change these kids. It's to figure out what it is they're trying to say, to figure out what their voice is, and then just help them become the writer that they want to become. And so there isn't one specific way to teach. So, every time you're trying to pay attention to the nuance of every student in your class and figuring out what it is that they want so that you can help them.

So, yes, I am teaching them, but you have to figure out how not to just override what they need based on what you think they should have. And it's fun. Art is instinctual. You do it because it feels right. And it's only later sometimes that you're like, "Here's why I did it" or "Here's the craft element." So, with my students, in teaching, sometimes I have to take the instinctual and really think it all the way through to explain it to someone else. And that's helpful for me, because then I realize what's underpinning those instincts that I do in my work. It helps me when I go back to write.

And then also, just teaching young people. I'm 44 and unless something weird happens, I'm just going to keep getting older. And my students are always going to be at this age where they're discovering new things and they're bringing the world that they know into the classroom. And that's just super helpful for me. It keeps me constantly considering what experiences they have that I need to consider. It's great. I wouldn't give it up.

TF: All right. Thank you so much for being here today. And thanks everyone for listening. Kevin, I hope you get to join me again in a future interview. And thanks again for being here.

KW: Oh, thank you so much. I loved it.

TF: And just to remind everyone, you can purchase, download, and listen to Now Is Not the Time to Panic right now on Audible.com.