Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

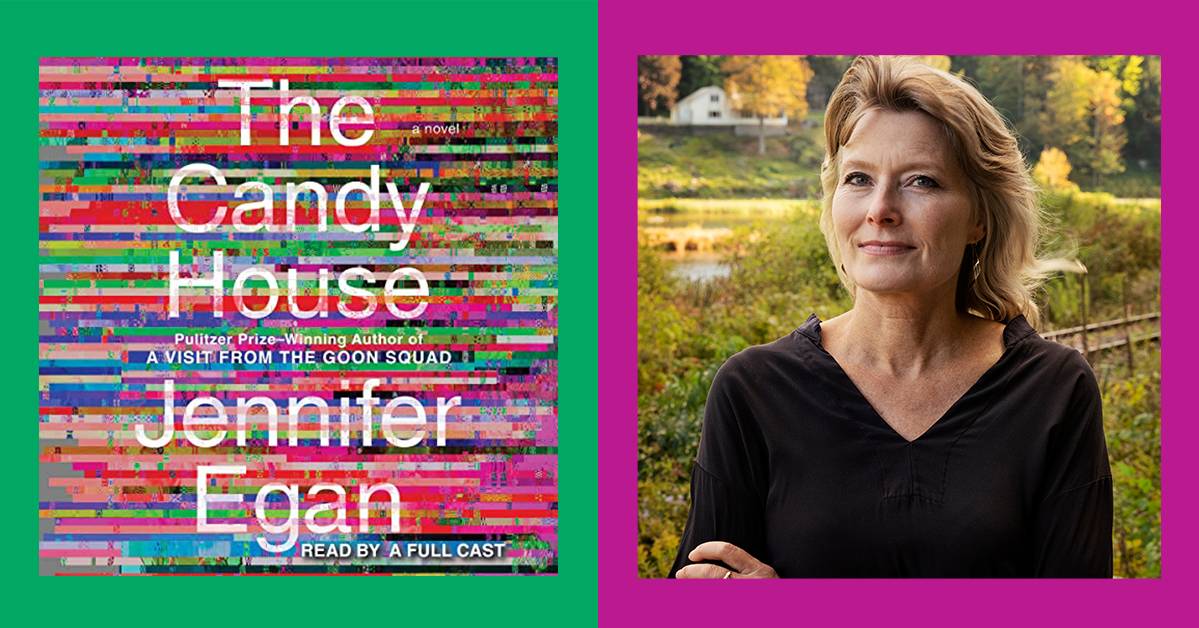

Tricia Ford: Hello, this is Tricia Ford, fiction editor here at Audible. And with me today is Jennifer Egan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer you might know from novels like 2010's A Visit from the Goon Squad and 2017's Manhattan Beach. I'm thrilled to have this chance to sit down and talk with her about The Candy House, her new novel where, in a very near future, a brilliant tech genius has created a social media company named Mandala and a seductive new technology he calls Own Your Unconscious. Its users can upload and access every memory they've ever had and share them in exchange for access to memories of other users. Welcome, Jennifer.

Jennifer Egan: Happy to be here. Thanks.

TF: Now this is undoubtedly one of the most highly anticipated books of the year, in part because it's a companion or a sibling novel to A Visit from the Goon Squad, which is kind of unexpected for me. What was the inspiration? Why did you bring some of these characters back and why now?

JE: Well, I had never really left them. The nature of Goon Squad is that it's pretty open-ended. I mean, every chapter is from a different person's point of view. Although I felt that the story arc had a kind of conclusion, none of those lives were concluded. So there was an inherent open-endedness to that book that had me thinking beyond its edges by the time it was published.

TF: Wow.

JE: I wrote several of the first drafts for this book in 2012 and 2013, at the same time that I was writing a first draft of my historical novel Manhattan Beach. Then Manhattan Beach really took over. It was so much work, because of all the research. So I returned to those first drafts years later, like 2016, and I hadn't even typed them up except for one which had been published.

So I typed them up and I took a look and said, huh, all right. The material felt alive. There was more to explore, so I kept going. My decision-making is often that way. It's very inductive and kind of reactive. I'm looking for the action, if you will, in my own head and on pages that I've created. And then I try to follow that action into a work that will be fun, hopefully rich, with a strong girding of ideas, but most of all people that are worth reading about.

TF: Definitely true in this case. I found it really interesting who reappears and who doesn't, and also how the two are very similar and very different. And I think that bears some discussion for anyone that might not be familiar with the structure of each story and what influenced it, especially the musical influences.

JE: Goon Squad is really a book about the music industry, particularly in its relationship to time. The Candy House is really not about music. And if I conceived of Goon Squad as a book about time, I conceived of The Candy House as a book about space, and I think that's why the word “house” is right in the title. Goon Squad has a structure that is pretty directly a concept album, in which a big story is told in small pieces that sound very different from each other. The goal was, just as in an album, contrast. You want songs to be juxtaposed in a way that wakes you up. So with this one, which is not specifically about music, the question was, what is the appropriate structure for this?

And that took me a while to understand, but I came to feel that it's very much about moving among worlds. It's sort of moving from one space to another in which those spaces feel like different worlds. So that is more of the structural idea behind The Candy House, which is very much about moving among worlds and consciousnesses through portals. And there's a lot of Dungeons and Dragons in the book, this idea of drawing worlds on graph paper and moving from one world to another.

TF: Definitely feels that way.

JE: I did not want to write an echo of an earlier book that would not be satisfying. I really thought it has to be a different book. For example, there's absolutely no need to have read Goon Squad to read Candy House. In fact, I have a feeling it might work better going the other direction in terms of just reader surprise and satisfaction. The narrative approach of Goon Squad is that each chapter is about a different person. Each chapter stands completely on its own, because if I'm going to ask people to start over again and again, I feel like I need to provide total satisfaction every time. And then finally, and this is the trickiest one, each chapter should feel like it's kind of part of a different book. In other words, the world of it should feel different.

And as my imagination moved beyond Goon Squad, whether or not I was able to revisit people, once again, felt very reliant on whether I could find a technical approach that would let some aspect of their lives really live on the page.

"Each chapter stands completely on its own, because if I'm going to ask people to start over again and again, I feel like I need to provide total satisfaction every time."

TF: The Candy House is a brilliant multi-cast production. There are more than a dozen narrators in this recording. It adds so much richness to the story, and because of the distinct chapters, every chapter stands out, having its own voice. Why do you think it works so much better? And do you think of it as kind of a projection or a bigger focus on audio in particular?

JE: Well, one thing that's interesting is the books are far enough apart in time in terms of their publication, so 12 years. It speaks to how audio has exploded in those years. So that's a really heartening and exciting part. I didn't even get an iPhone till 2012, so I had never really listened to an audiobook on my phone before that. It's just a thrilling consequence of what can be a really annoying fact, which is that we're soldered to our phones. It's possible to listen to fiction constantly. So to me, it's an exciting celebration of the way in which this aspect of the market has become so strong and creative. And obviously, the multiple points of view really invite that.

TF: There's an art to it and it definitely shows through many times.

JE: I agree. I listened to all of them and helped with that. My involvement was kind of minimal, but I so agree with you. And it was also a chance for me to discover a bunch of young actors that I didn't know of. So that's very thrilling. As someone who listens to audio basically at all times, unless I'm reading, writing, or interacting with a human being, I can tell you that the voices are so critical. If the voice isn't right, for me, it actually feels like I'm being poisoned, so I'm really grateful for the care.

TF: I totally agree. It really makes or breaks it. A great book can become a not-so-great book, and something that might be considered fluff or not serious can really be elevated to a great production and a source of entertainment.

JE: Totally. I just listened to all of Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes right from the beginning to the end, read by Stephen Fry. And it is so dynamite. Fry also has written introductions to a number of the volumes. So we get Fry's voice and writing all the way through. It is so great. I just love doing that.

TF: I agree. Mysteries, especially British mysteries, are one of my favorite genres to listen to, more than reading for sure. Back to The Candy House, this idea of owning your unconscious, if this were something real, would you use it? And what are the positive aspects as well as the negative?

JE: I would certainly use it, is the answer. Just to define what the device is, it is a beautiful one-foot-square cube, which in just four hours of electrodes on your head you can upload the entirety of your consciousness. No one else has to see it. It's just there. And the reason I would do it is that I have a lot of dementia in my family. And one of the positives that is posited in this novel is that, if you keep uploading your consciousness, if you start to experience dementia, you can re-infuse this complete and healthy consciousness into your brain and be cured. That's a little hard to resist.

The other exciting thing that I would want to partake of is that I often feel that my memories are so limited and kind of shop worn. So I love the thought of being able to see things anew through my own eyes, just to broaden that landscape of my memory. The second part of the invention is a little bit more tricky to decide. And that's the question of whether to join the collective consciousness. If you're willing to share your consciousness to the collective, you have access to everyone else's. It's all anonymous, except not really because you can pretty quickly tell whose eyes you're looking through. And facial recognition technology makes it possible to do searches on people and on places and times. This all activates my curiosity hugely, like how could I resist? I'm someone who walks down the street in Brooklyn at night, glancing into lighted windows because I want to see what people's lives are like. So I would have a really hard time passing up the chance to actually do literally what I do in writing and reading all the time and what makes it so fun, which is experience the consciousness of another human being.

Luckily I think it's actually inconceivable that this invention would ever happen. As I understand it, and I know basically nothing about brain science, we don't understand the brain very well. So I don't think we're going to be able to do that. But the thing is that none of this is really that different from what the internet already is doing. There's too much consciousness at our fingertips. As a writer, it's all too easy to start reading your Goodreads reviews, feeling gutted by mean things people say, but in a way, they're saying them in private. There's no reason we should be reading them. That's a case of just entering into someone else's thoughts in a way that's not appropriate. The cruelty of social media is so much about that too.

TF: In this story, there's a few different types of characters. There's the proxies who are professionals, who cover up for the eluders by maintaining their abandoned identity. The eluders are the people who are refusing to let their consciousness be uploaded or be accessed by others. So these proxies who are protective of the eluders are the fiction writers. Do you see yourself as a proxy? And what are you trying to protect?

JE: Well, first of all, the eluders are even more radical. They're saying “I won't upload my consciousness.” In a way, that sort of goes without saying. What they're saying is I don't want to be me anymore. Now that my identity is in the collective consciousness through the points of view of all these other people who have shared, I don't actually want to be that person anymore. It's “I feel tired of that person.” So what an eluder does is actually sheds their identity altogether, leaves it behind as a figment of the internet, takes on a new identity and then hires or employs either a program or an actual proxy to impersonate them online so that it's not known that they've disappeared, except by those who would normally see them in real life. One person likens it to an animal caught in a trap chewing off its leg as the price of escape.

It's a big ask to leave your identity behind. It's like a witness protection program. That would be the analogy. That's a huge step to take, and a lot of people don't do it successfully. They don't want to stay away from their old identities. And there's a lot of interesting drama that could be explored there. So the proxies are the ones who impersonate the eluders, and I identify a lot with that. Partly, because I was a private secretary to a writer for three years, and I had to write letters in her voice and sign books as her. That kind of ventriloquism is so much what fiction writers do. That's what we're doing when we invent characters, but it never feels like inventing. It feels like discovering. So I love the thought of fiction writers working for this not-for-profit that enables people to elude by impersonating them online.

TF: Interesting. Another big theme is authenticity and wanting to experience that. And is this technology heightening that for reasons you spoke about earlier? Your memories aren't preserved indefinitely without this tool, so maybe it is a path towards a more complete picture of yourself which might be considered more authentic. What do you think?

JE: A critic named Daniel Boorstin wrote about this really eloquently [in The Image, published in 1962]. So before mass media. He was really just responding to television and advertising. And he basically said that, the more we present ourselves for the camera for each other as images, the more we feel a kind of fakeness about those experiences. So this really explains reality television. This hunger for something that feels real, which the multinational corporations that create mass media understand that they have to give the feeling of providing, or they will not make money. So that is a fascinating thing. Obviously not my invention at all, but something that I think about a lot.

"We are drowning in information. We can know so much, much more than we can process, and it does not necessarily bring us any closer to some sort of universal truth."

So in some ways I was exploring that idea in this book as well with this machine, which in a certain way absolutely offers authenticity as you say. Here are your memories, here is raw consciousness. There's also an idea that I posit in the book in a chapter that's taking place in 2035. It is announced that social media is essentially dead, because compared to the collective consciousness, it seems really fake. So, once again, the search for authenticity is a very vexed and difficult one. But very fun for us fiction writers to explore.

TF: It is. And there's authenticity that's not the same thing as being right. Someone could have an authentic experience that's very opposite of someone else's authentic experience of the same event.

JE: I mean, QAnon followers passionately believe that they are seeing the authentic truth. I think that's something that's so important to remember because, once again, we are drowning in information. We can know so much, much more than we can process, and it does not necessarily bring us any closer to some sort of universal truth. The data-driven approach to human behavior that is more and more prevalent reveals many truths. It's fascinating to hear about demographics. They are very revealing.

TF: I love how all of these ideas are explored, but in this story, the characters are what shine. Maybe we'll never know true authentic identities of every one, but you do get bonded to these characters. They're real characters with heart and you will care about them.

JE: That's all that matters in fiction. We're talking about ideas and that's really fun, but that is worth nothing if the characters are not compelling. The secret lives of human beings are the stuff of fiction. That is why we read fiction, to have the experience of being inside the mind of another human being, which is the one thing we can never actually do in real life. And so it's the ultimate voyeurism from my point of view. I like the extremes of being in points of view that are really far from my own. And in the end, this book is all about letting those points of view converge into one story.

TF: I totally agree. Now we talked about this a little bit earlier, but do you see these characters or the children of these characters showing up in a future book?

JE: It's hard to know whether I could pull off a future book because there's so many things that have to fall the right way for that to work. And I actually didn't know for a while that I would actually collect these new imaginings into what became The Candy House, because I would only want to do it if it felt like it was its own thing, just as fun as the others. Fun is the key. I do have a few glimmers of people that I want to follow out of The Candy House and Goon Squad into other narratives. And that's kind of where it starts.

These are books really built around curiosity. The organizing principle is you see something out of the corner of your eye, and you briefly think, “Huh.” And then suddenly in the next chapter or later you're plunged into the middle of that situation or that person's point of view. So there are a couple of people like that that I have in mind. I feel like with each one it gets actually harder, because the other thing is, I want to keep finding new narrative approaches so that I can maintain that feeling of all of these texture changes. And so there are a lot of ifs there. But my curiosity is still active in the realm of this material. So I think it's possible.

TF: I love that answer, because if you had it perfectly planned out, honestly, I might have been a little bit disappointed. I like that there's some surprise and organicness to the process and it reveals it to you in its own time, not in a prescribed time.

JE: That is how I write. There's a lot of organic exploration or what I think of more and more as improv.

TF: Now, it sounds like maybe there'll be another work of historical fiction in between.

JE: We'll see. I think so. I'm actually curious to try to move forward with some of the characters from Manhattan Beach, my last book. I love the thought of writing books set in the '60s. I'm just curious about following American life forward. I was born in '62, but it feels like that's the movement of American life that I've really witnessed. And then I also love the thought of writing about 19th century New York. I'm crazy about 19th century fiction generally. I tend to listen on audio, and these are huge books. They're hard to carry around, 18th and 19th century fiction.

Audio has let me revisit the evolution of the novel in a way that I probably never would have in my adult life otherwise. I recently listened to all of Clarissa by Samuel Richardson on audio. I think it's 110 hours. It was an incredible experience. And so I'm toying with that as well. Lots of ideas for sure. I'm not sure which will be next.

TF: With the collective consciousness, the first thing that came to my mind as a former psych major and a fan of studying Carl Jung, I thought of the collective unconscious immediately. It was almost like your collective consciousness is an inverse. It's the individual's actual consciousness forming this entity of the collective consciousness versus being all the same underneath it all.

JE: I'm playing on that term of the collective unconscious. The idea of the collective unconscious is so fascinating. I think of about it because I'm aware so often of creating symbolism and connections in my work that don't happen consciously. Just as one example, I have found that I use names in ways that I don't realize are sort of obvious until later. So here's one example from A Visit from the Goon Squad, since both of these characters actually appear in The Candy House. A Visit from the Goon Squad begins with a woman named Sasha and a guy named Alex having a one-night stand. Both of those characters reappear in The Candy House, but what I didn't know when I wrote that is that Sasha and Alex are the same name. Sasha is a nickname for Alexander.

One way to explain that is the collective unconscious. I tend to think more in terms of just the unconscious. So I guess I lean more toward Freud, but what I feel very much is that we have such a cultural unconscious. Maybe it's all the same thing. Maybe what Jung meant was a cultural unconscious, but where that is really revealed is through fiction. What are people remembering? What are they nostalgic for? What are their cultural points of reference? The place where it's all revealed is in fiction, because fiction is a kind of dream distillation of the culture around it.

TF: I love the play on it and the modernization of it. What is your process for writing and how do you approach different forms of writing?

JE: My process is pretty much the same no matter what I'm doing. I always write first drafts in long hand for fiction. Since I write original fiction without a plan, what I'm doing is really just trying to generate material that feels alive enough to actually work with. So I do it in a kind of blind way of horrible handwriting. I can't really read it very well. The act of writing cursive is very meditative. It has a flowing quality that is very useful to me. I try to write five to seven pages a day of a new material if I'm in that mode. The next day I reread what I've written, which is just a process of getting back into the flow, and I push it forward another five to seven pages. I do this until I have a draft.

Once I have a draft, I type it up and that's the phase I'm at now with this project I mentioned. But even as I'm typing, I'm still not in a position to judge the value of it, interestingly. I try to just be a typing machine and I don't fix or change anything because I don't know what I'm doing yet. It's only when I have it typed and I then read it through that I really can know whether it's worth pursuing. And then once I've done that, if I think it does have potential, I make a very detailed outline, the first of many, which will guide me through my revision process. If it's a shorter piece, I don't really need to make an outline, but I might make a few notes about goals. And then I head back through and start revising, which I generally do by hand on hard copies.

The reason I do that is so that I can access that sort of meditative dreaming part of me, which is where all of the good ideas come from, and the worse the material, the more I need those good ideas. Once I've gone through all of it once again and completed my revision outline, I read it through again and I make a new outline, hopefully it's shorter. And one other thing I should mention, which is ridiculous in the case that The Candy House, which is dedicated to my writing group, is that I solicit feedback all the way through. I bring in material. They are my collaborators. They have slapped me out of some really bad ideas, very early, which is really helpful. I don't assume that just because I think something is happening on the page that others will agree. A lot of people give me feedback on my projects before they go into print.

TF: That's amazing. I love that. Because I think some people might imagine famous novelists like yourself to be stingy almost, like, you're too good for that. I love how you're not at all like that.

JE: The minute I start thinking I'm too good for criticism is going to be when my career is ending. Because that would mean that I am too afraid to be criticized, and believe me, this is not comfortable. I don't want pages of notes. I want it to be perfect. It's awful. But it's essential. You know? The one other reason that I really have to do this is I am the opposite of an auto-fiction writer. I don't write about myself. I don't write about people I know. And for me, writing is all about the joy of being delivered out of my life and out of my brain. As a matter of due diligence, I have to have other eyes on what I'm doing. I write more often than not from the point of view of a man. I need the feedback to make sure I'm not getting it wrong.

TF: That's amazing. And it's inspiring to many people who are intimidated of the process, thinking you have to do it all on your own. It's not divine intervention, it's work. And asking for help is part of doing anything.

JE: Everyone is different. It's so interesting to hear how different people do it. But trial and error is basically my methodology. If I were a different sort of person, I might not have the stamina to persist through that sense of failure. The feeling that I'm solving a problem, that I can make it better, is what keeps me going. I've had sessions over the years with my writing group where they really didn't like something and I'm just enraged. My inner dialogue is, “I'm done, we've had a great run, but it's over, you just don't understand what I'm doing.” But even as I'm having those thoughts, I can feel an almost scurrying in my brain. It's like little mice running around an attic. And that scurrying is the problem-solving side of myself kicking in, where I'm thinking, "Ah, but wait, I could try that. Oh wait. But what about that?" Even when I have no confidence and not much hope, I just won't stop because I feel like maybe I can make it better.

TF: I'm glad that you don't stop. And I think that urge in you really does translate into great storytelling. I think if it were easy, if there were no resistance, that's how you come up with diamonds, so to speak. Now, for all you listeners out there, you can find Jennifer Egan's novels, including The Candy House, on audible.com right now.