Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

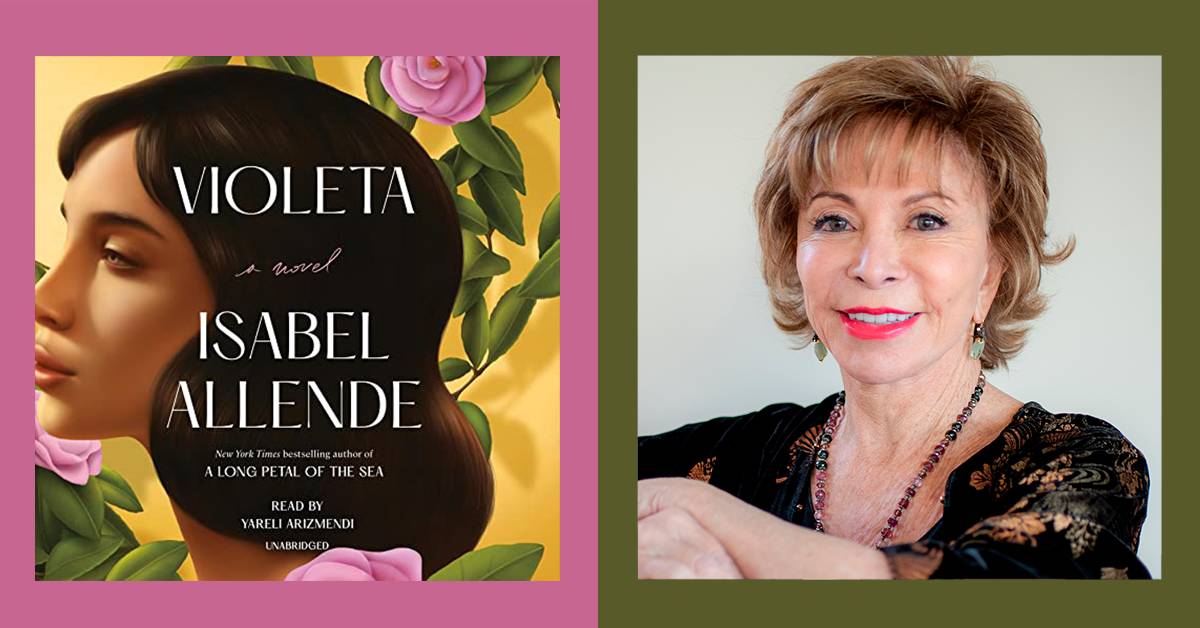

Christina Harcar: Hello, I'm Audible Editor Christina Harcar. Today, I have the rare privilege to speak with Isabel Allende about Violeta, a story that immerses the listener in the events of 1920 through 2020 as described by a passionate, flawed, resilient, and unforgettable narrator, the title character. Listeners may already be familiar with Isabel Allende's previous bestselling and critically acclaimed works, including her first novel, The House of the Spirits, and also Daughter of Fortune, and A Long Petal of the Sea, just to name a few. Welcome, Isabel, and thank you for speaking with Audible.

Isabel Allende: Thank you, Christina, for having me.

CH: So let's dive in and talk about Violeta. It's framed as a letter written by a 100-year-old woman. Why did you choose this particular hundred-year time period of 1920 to 2020 to frame the story?

IA: When my mother died shortly before the pandemic, she was 98 years old, and she was born in 1920. She was a very special person. We had a very intimate, very deep relationship, mostly writing letters. We wrote to each other every single day for decades. When email came around, my mother went crazy. She would write to me sometimes two or three times a day. So it was an ongoing conversation that kept us very close emotionally, although we were separated most of our lives.

People who knew this story told me at the time when she died, “You have to write about your mother based on those letters,” but I just couldn't do it, Christina. I was too close. I was hurting because she had died, and I miss her to this day terribly. But I created a character that was very much like my mother, who lived at the same time, in the same century. That was a fascinating century full of important events. Two world wars, the Holocaust, the Cold War, the atomic bombs, technology and science that changed the world completely in my mother's life.

"You have to start from a generous place in your heart: not judging, not trying to punish, not trying to control or change anything. Just be generous."

So I wanted to tell about that, but I wanted a character that would be like my mother with a life that she would be more in control of, because my mother was never economically independent. First, she was dependent on her father, then first husband, then second husband, and eventually me. So she could never quite develop her incredible talent, and her ambition, and her capacities because she was somehow submissive because of that.

CH: Well, first I would like to thank you for sharing that, and to offer you personally my condolences on that loss, which anyone who has lost a mother knows, you have lost your greatest cheerleader. You will always feel that loss, and I am sorry.

IA: Yeah. It's very hard. And you know what I miss a lot, Christina? The letters I wrote to her every day. Because it is as if time goes by and there is no record of anything. Days sort of blend into each other. I can't remember what happened two days ago, but before, I had a letter that day, so if I needed to remember something, I could always go back to the letter.

CH: I noticed when I was listening to Violeta that there was an undercurrent of grief. I thought that I was putting it in myself because it has been such an odd two years, but now I think I really admire the way you, not just as an author, but also as a daughter, transmuted that human grief into something that stands and also explains how this time was.

IA: And also Violeta is writing when she's dying. She's saying goodbye in a way to the person she loves the most in the world, her grandson. So there is grief also, some pain in the fact that she's leaving. And although she's not afraid of death, she's also very much in love with life.

CH: That comes across, and also I'm delighted that you were able to give the fictional Violeta agency that her nonfiction inspiration didn't have. And so I wanted to kind of talk about that, the idea that Violeta's writing a novel to, in a way, the love of her life, this beloved grandson, Camilo. I don't want to give away too much. What do you think is so magical about the idea of writing a letter to our beloved ones of the future? That seems to call to you. Why is that so magical?

IA: You know, it's an art that has been lost. People communicated in writing before this technology ended with letter writing. My mother, as I've said, was born at the beginning of the century, in 1920. She learned calligraphy at school. You had to write beautifully and the handwriting had to be perfect. You couldn't send a letter with a stain or with something that you had erased. It had to be clean. Grammar had to be perfect. A spelling mistake was an insult. So that idea of sitting down and communicating beautifully and thoughtfully with another person was part of my upbringing, and was part of my life for as long as my mother lived, for most of my life. And I miss that, and I think that humanity is missing it also.

"I am an audiobook addict. I love audiobooks because I love a voice telling me a story."

I love my computer. I love the fact that I can write so fast and I can correct and move paragraphs. All the things that I couldn't do when I was using a typewriter. But I have lost not only the art of letter writing, but also a way of thinking. Before I sat to write with an idea in my head. And before writing down a sentence, I had it in my head. The sentence was already formed, and the paragraph and the story were already somehow formed inside me.

Now, I just plunge into the keyboard and it doesn't matter because I can always correct and overcorrect and erase as much as I want. So that has also been lost. That means that there are no manuscripts. In the future, when some people want to study authors of today, they will not find manuscripts. They will find a final version of the book. We will not see the process. How did that author get to that final version? It’s lost.

CH: Yes. I still write with a fountain pen, as an aside. And I agree that while my computer is a tool, my fountain pen is my friend. It helps me get things onto paper.

I wanted to talk a little bit more about family, but now I'd like to switch to your fictional family, the Del Valle family. Listeners have been familiar with this clan, and its related branch, the Truebas, since The House of the Spirits. And there was yet another branch of the clan explored throughout Daughter of Fortune and Portrait in Sepia. I'm wondering what drew you to this branch that gets developed in Violeta. Why is now the moment to bring this branch of the Del Valle family into the present?

IA: I don't know. When I wrote The House of the Spirits, Clara Del Valle, who is probably the main character in the book, is one of 12 children. That is incredibly good material for me, because I can exploit those people. In real life, my grandmother was the youngest of 12. Most of those siblings had weird lives. I mean, with a family as crazy as mine, I have material forever. I don't have to imagine anything. No need to invent.

The idea that the Del Valle family has crept back into my books and might in the future come back again is because I have so much material. I have 12 people that I can use. You know, there's a little story here in The House of the Spirits: Severo and Nivea Del Valle are a couple, and they are the old parents. And in Portrait in Sepia, which I wrote much later than the The House of the Spirits, I picked up Severo and Nivea as young people when they were in love and young.

CH: And we got to see his military service. I thought that was most thrilling part of the book. I didn't know anything about that Pacific conflagration.

IA: Yeah, and then he loses a leg. But then, in The House of the Spirits, he has two legs. So how did he recover that leg? That's magic realism, I don’t know what happened there.

CH: Yes. And it's a happier healing up process than anyone in the Buendía family ever experienced too, so I'm happy. I don't begrudge him for his leg. He's a wonderful character.

You touched upon the parallel between your actual family and the Del Valles. How does it feel for you to write in fiction about events that may have been painful and global in real life that affected your family?

To me, this was the book where you dealt most in depth with the events of 1973, and I was wondering if that was hard.

IA: No. It's very cathartic. I keep writing about certain things. Certain themes always come back. And when I have written books set in South America, I always end up talking, for some reason, about those terrible years: the '70s and the '80s in which so many countries suffered horrible repression.

"Never my intention is to teach anything. Who am I to do that? I have questions. I don't have answers."

Recently, I have been writing about immigrants and about refugees in Central America. The genocides that the military committed in Central America are horrible, and we know very little about that. The same thing with the dictatorships of South America: Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, we know some, but people who have lived that can never forget it, and so it keeps coming back. My books are always about more or less the same subjects. It's death, violence, love, loyalty, courage, strong women, absent fathers, love. Love in all its forms. I think that's what I write about mostly.

CH: Yes, and it makes this fan very happy. It segues beautifully into my next question. What was your favorite moment of Violeta to write? Which moment gave you the most happiness to put down on paper?

IA: You know, I like the parts of the book where there's humor, where she makes fun of herself and of life. She has enough distance in age to be ironic about her own mistakes. Those are the parts I enjoy writing, because I can see myself there. For example, when she talks about Solida, who is Julian's lover, or when she manipulates all that relationship, or when she takes revenge of Julian, all of this is done tongue in cheek. Those are the parts I love most. And the parts I suffer most, of course, are when she suffers. When her son disappears, when her daughter dies. Those are the parts that I cry with her. But I like the parts where I laugh with her. And I applaud her. I applauded her because I said, “Oh wow, I wouldn't have thought of this.”

CH: I felt that way listening too. There were times when I thought, “Oh, no, don't do that.” Or, “Can't you see that?” But I felt such triumph and such oneness with her. Immersive does not even describe how this book felt to me as a listener. So other listeners: dive right in. I want to thank you for your answer to the previous question, which in my mind I was still kind of replaying, because it hit me so strongly—where you said that your themes are always about all types of love and violence and death.

IA: And losses, a lot of losses.

CH: I'm still so fascinated by your mother in person and Violeta on the page, because it strikes me in talking to you that they both always had an impulse to be generous. That no matter how much they lost or survived, there was still something else to be given. That the flower of life was still there to be handed along to the next generation. And I feel like that is such a generous impulse. That's how your books feel to me: that you are trying to empower and protect people through these stories.

IA: It's not a conscious proposition. I don't think that way, it just happens. I think that what I cherish in life and what I fear in life come through the lines. In between the lines you can read about me also, but that happens with every author, I suppose. You reveal yourself in every story: Why do I choose that story and no other? Those characters that have to say those things and nothing else? It's because I'm trying to say something, but I don't know what. I let them be. I let them speak for themselves. And in many ways, they represent me also.

The mantra that has guided my life since my daughter died is her mantra. She was a psychologist, and I would call Paula sometimes with problems because I was married to a man who had three addicted children. So our life was one tragedy after the other. I would call my daughter—who was living in Spain at the time—crying on the phone, trying to explain the drama that we were going through. She would listen very carefully, and then she would say, "Mother, what is the most generous thing to do in this case?" And if you apply that formula, it always works. Always.

Sometimes the most generous thing to do is not to say yes or to give. Sometimes it's the opposite. You have to start from a generous place in your heart: not judging, not trying to punish, not trying to control or change anything. Just be generous.

When I created a foundation to honor my daughter, the mantra of the foundation is “What is the most generous thing to do in this case?” That has been so rewarding in my life, Christina. It has been a blessing, because for everything you give, you get 10 times more back.

CH: It is a miracle how generosity does work that way.

IA: You know, Christina, meanness works the same way. If you are mean, you get back meanness.

CH: I know. And I shouldn't laugh, but I'm glad for that too.

IA: Yeah. I'm glad too.

CH: Let's talk about listening. Violeta is narrated by Yareli Arizmendi, who is a top-tier narrator and a wonderful actor. So how does it feel for you when you hear her perform your words?

IA: Unfortunately, I have not heard her, because why would I listen to my own books? I am an audiobook addict. I love audiobooks because I love a voice telling me a story. And sometimes I have the audio and the book, so I check things. I listen to novels, mostly, and short stories in my car. There are thousands of authors I want to read or hear from. Why would I listen to my own stuff? I wrote it. I know it. No surprises there.

"My job is to choose among those millions of free lives that I can use, and transform that into written words. It's a beautiful, beautiful craft."

CH: I love that answer. That may be my favorite answer to that question of all time, not that it's a competition. So what do you love? What have you been listening to recently?

IA: I love everything I read. You know, I remember when my grandchildren were little, I heard Harry Potter. I didn't have the patience to read it, but I listened to it. It was like a “zzzzz” inside my head all day because I needed to talk with them about the only thing that interested them—the only thing—and that was Harry Potter and the people around Harry Potter. So I remember that was my first encounter with audiobooks. And since then I have been a total addict.

CH: Were you a Jim Dale listener?

IA: Yes.

CH: That hooked a lot of people. Just for the record, we're huge proponents of everyone getting their stories however they want them. We all read and toggle back and forth between the audio. Any story time in life is a gift. That's not our official motto, but the Audible editors pretty much live by that rule.

IA: You know, and as you get older—I'll be 80 this year—it's harder to read, because the print is very small. Your eyes get tired and sometimes it's even hard to hold a book up because some books are 600 pages long and are like a brick. So the audio is so relaxing and wonderful, somebody telling you a story like when we were kids.

CH: It does feel good. I'm very happy that you hinted earlier that you may be going back to the Del Valle family. That's great to hear. I'm just wondering, because I read the interviews and I know that you tend to start things on January 8, do you know right now what you're going to be working on on January 8, 2023?

IA: No. But I know what I'm going to be doing in '22, which is this year.

CH: Do you feel like sharing that tidbit?

IA: No, but I can tell you that I have another book that is already finished. I wrote it last year. It's now being translated into English so that my American editor can read it. She doesn't read Spanish and I write in Spanish, so once she reads it and we talk about it, I will have a final version. And then I can talk about that book. That will probably be published by the end of the year.

CH: That is wonderful to hear. And for that secret book in your creative womb right now, we don't need to hear about it, we just wish it well. We understand.

IA: Thank you so much.

CH: I hope it's everything you want it to be. I have one more question. Is there anything else you want listeners to know about Violeta or your books or about your message?

IA: I want them to know that there is no message. Never my intention is to teach anything. Who am I to do that? I have questions. I don't have answers.

But I am addicted to stories. I love hearing about other people's lives. And the first thing I do when I meet someone is say, "Tell me your life." Everybody wants to tell their lives. My job is to choose among those millions of free lives that I can use, and transform that into written words. It's a beautiful, beautiful craft. And I love it. I enjoy so much the process that I wish that my readers will enjoy the process of reading, as I do the process of writing.

My goal is to grab the reader by the neck, and to not let that reader go until the last page. If I can achieve that, I'm so happy. Now, is that a good book, a bad book, a better book? Is there a message? Who knows? It depends on the person, on the reader—not on me.

CH: On that very inspirational note, I would like to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your time in answering these questions, and for your candor, and for the story that grabbed me by the throat and didn't let me go, Violeta.

IA: Thank you, Christina.

CH: And, listeners, I want to let you all know you can get Violeta on Audible now.